The Journal Keeper

Tinto Snivello, a low level clerk in the Office of Citizen Services, aspired to the creative class and acceptance within the City State intelligentsia. But, while proficient in menial tasks, he lacked the inspired skill and dedication of true genius.

His aspirations seemed doomed to the purgatory of the unrealizable until the day that the artist, scientist, and inventor Donatello Di Vulgi walked through his office door. Di Vulgi was in many ways an ordinary looking man, but his eyes and his words betrayed a unique and powerful personality.

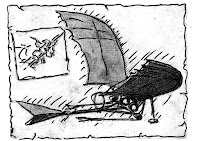

“I have many thoughts, ideas and imaginings in all fields of human curiosity,” the scientist said with foaming enthusiasm and feverish movements. “In botany and anatomy, in mathematics and music, in geology and cartography and even for innovation in the visual arts.”

He then described the detail of some of his inventions and designs, often referring to drawings in charcoal and ink as well as pages of notes and equations that the passionate scientist pulled from a large leather portfolio. When he talked about ideas and images, the man was elevated and joyous, but he then came down to earth and a deliberate speech to ask Snivello a particular question.

He then described the detail of some of his inventions and designs, often referring to drawings in charcoal and ink as well as pages of notes and equations that the passionate scientist pulled from a large leather portfolio. When he talked about ideas and images, the man was elevated and joyous, but he then came down to earth and a deliberate speech to ask Snivello a particular question.

“What do I do with them ?” he asked. “Can such things be given protection from appropriation and theft?”

Snivello regarded the creative process as a mystery and a supernatural practice and could not relate it to the substance of the legal papers, deeds, and contracts that filled his office shelves. But he was intrigued by what he saw and did not want to send the strange man of ideas away.

“We cannot provide you with particular legal protection for mere thought and imaginings,” Snivello said with the weight of a duly deputized City State clerk. “But I would recommend that you place these papers in the care of our office such that we might date their receipt and provide them with the security of our space.”

“With no other option to consider, I will do it,” said the scientist inventor with some pause. “At least for now.”

Di Vulgi’s hesitation and qualification haunted Snivello the rest of the day, and when the clerk closed the office for the night, he found himself taking the scientist’s scribblings home for further study. Unsure of how long he might have to examine the papers, Snivello made a copy of each one in the journal notebook that had sat unopened for years on his bedroom desk.

The next morning of his way to the office, Snivello stopped by the inn as was his custom. But in an uncustomary way, he fell into animated conversation with the innkeeper and other patrons. Normally awkward in social interactions, Snivello found that he had new insights to offer on subjects of broad interest and could engage others with proposals for improvements to life in the City State.

The next morning of his way to the office, Snivello stopped by the inn as was his custom. But in an uncustomary way, he fell into animated conversation with the innkeeper and other patrons. Normally awkward in social interactions, Snivello found that he had new insights to offer on subjects of broad interest and could engage others with proposals for improvements to life in the City State.

“That is an excellent idea: pure genius,” one patron said as he offered to buy a beverage for the clerk.

“I must decline as I am on route to my duties in the service of the citizen,” said Snivello , sensing a new situation and the new era ahead.

In the months that followed, Di Vulgi visited Snivello’s office regularly to deposit new drawings and texts and to describe his ideas and inventions with profundity and always with enthusiasm. Each time, Snivello would take the notes and drawings to his home, adorn himself in the garments of an artist, and copy the inventions and ideas into his own journal.

Soon Snivello came to depend upon a recounting of Di Vulgi’s ideas in the taverns and inns as a means to gaining greater and greater favours, food and drink from appreciative admirers. He spoke those ideas with increasing authority and ease leaving all, including at times Snivello himself, convinced that the ideas were his own creations. Then, one day, the situation changed.

“I appreciate your past service, my friend, but I have decided to take greater personal control over my works and would like them back,” Di Vulgi announced one morning shortly after the Office of Citizen Services opened. “I am preparing a library such that the collection might be preserved as an assembly and thus regret that I will not be returning in the context of this business.”

Snivello pulled out the wooden crates with the papers and quietly said good-bye to the scientist as he walked down the road. Then, realizing the blow that the scientist’s new course would have on his life and status, the clerk called after him.

“I must insist that you bring your papers back to this office and continue to deposit your musings and inventions with us,” said the Clerk in an anxious tone. “This information is of great public import and cannot be trusted to your personal concern and judgment.”

“I do not understand,” said Di Vulgi. “These are my works and should I not have some say in their administration and distribution.”

Despite Snivello’s threatening manner, the scientist continued on his way turning once to make a concession.

“I will consult with my family and my advisors on this matter and return,” he said.

The weeks that passed before their next encounter were painful and long for the clerk. His evenings were barren as he sat staring at the empty page of his journal notebook and his days grew increasingly awkward as he was forced to face his one-time admirers and beverage sponsors with no new thoughts or ideas to share. He grew frustrated and angry.

Di Vulgi, however, was fully occupied with the process of actual invention and creation as well as the less pressing issue of Snivello’s attitude and need, and he did not regard the time passed as significant.

“My family and friends have found a constructive solution to your issue,” Di Vulgi said cheerfully as he entered the Office of Citizen Services. “We believe it appropriate to deposit the foundational documents and technical papers with your office such that they might inform further creation in the future while I will retain my personal musings, illustrations and applications.”

Di Vulgi also shared the written counsel and comments from his family and his advisors to attest to the diligence with which Snivello’s demands had been considered.

The Clerk, whose anxiety and personal strains swelled to crescendo, threw the papers against the wall and insulted the scientist with slur and menacing words.

“You are a wastrel and a hoarder,” said Snivello. “You will regret this decision, I assure you.”

The creative man, not wanting to aggravate the clerk further, bowed and bid him good day.

That night Snivello had no issue in filling the blank pages of his notebook. He wrote a long speech describing how the people at the inn and others benefited from the amusement and knowledge that came from the established process of deposit and sharing of Di Vulgi’s ideas. He condemned the scientist as selfish and secretive to the detriment of the City State, and finally he added quotations from the personal communications of Di Vulgi’s friends and family around Snivello’s demands, using them to illustrate Di Vulgi’s inclination to squander his time and divert his attention from needed invention.

Full of anger and passion, Snivello entered the inn the next day and jumped onto a table to deliver his speech before the packed room. He then methodically described the effect and importance of the invention deposit, copying, and sharing process that he had developed knowing that his admirers would understand and share his concern.

“We should mock and ridicule the secretive and difficult Di Vulgi,” the clerk concluded in a passionate shout that sent drool flowing down from the corners of his mouth. “The City State would be better off without his kind.”

A burly man who was one of Snivello’s greatest supporters and beverage sponsors was clearly moved by the speech. His faced twitched and his eyes bulged as he listened to Snivello’s demand for support and passionate plea. At the clerk’s call for action, the big man stood up and turned to the assemblage.

“This clerk is a fraud and has taken our money under pretense,” the man said in full voice. “Heat up the pine tar and pluck the birds.”

Buy the E-book

Buy the E-book